13.12.14

Solace Summit 2014

Source: Public Sector Executive Dec/Jan 2015

PSE’s Sam McCaffrey reports from the annual summit of the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives and senior managers.

If there was a recurring theme running through this year’s Solace Summit in Liverpool, it was ‘change’. Rising demand and plummeting funding means the public sector cannot continue as it has been, so the focus has shifted to transformation, change and redesign.

One of the highlights of the conference was a discussion session on that topic, Public Service Redesign. PSE contributor Barry Quirk, chief executive of the London Borough of Lewisham, who co-chaired an inquiry on public services for the Design Commission last year, led a spirited discussion on the topic.

Helen Lazarus and Gavin Pryke of the Design Council gave a fascinating talk on how services can be designed, followed by a funny and eye-opening presentation from David McNulty, chief executive of Surrey Council, who explained how he has helped overhaul the culture and services provided by the authority. More on that session overleaf.

LGA chair Cllr David Sparks addressed the Summit too, admitting that the LGA has “insufficient contact” with councils on a daily basis.

Cllr Sparks said: “I’m acutely aware that…one of the deficiencies of the LGA is the fact that there is insufficient contact on a daily basis with local authorities. That can lead to a situation where it’s almost as if we become a third estate in Whitehall and we have to watch that.”

On the devolution debate, he said he believes people identify with cities, counties, towns and villages, rather than regions. As a result, he said, devolution would look different in different places, and local government would need to argue for devolution in different forms. He also warned that gaining more powers and control over funding were not inevitable. He said the challenge was “to make sure people know how relevant local government is”.

“We have got to argue on the basis that it’s devolution to communities through councils,” said Cllr Sparks. “We have to anchor ourselves in local communities, not just because it makes for effective local government but because individuals relate to communities far more than they do to arbitrary boundaries.”

The level of demand is ‘crucifying us’

Coventy City Council chief executive Martin Reeves, a past president of Solace, chaired a session on demand management – addressing the ‘demand for’ not just ‘supply of’ public services. He opened the session with a call to arms: “We, as a sector, at senior leadership level, need to come up with an alternative to how we build different relationships with the people we’re meant to be serving, where they’re the heart of the redesign.

“[We must] manage and understand, through behavioural change and insight, the management of demand – which currently is crucifying us within local authorities and across the public service system,” Reeves said.

Dr Carolyn Wilkins, chief executive of Oldham Council, discussed the authority’s much-heralded journey to becoming a ‘co-operative’ council, re-shaping service demand as part of a changed relationship between the council and communities.

She said that previously when focusing on demand, they tended to have a rationing approach, which she said was more about optimising supply rather than truly addressing demand. Her presentation showed that as long as public sector budgets continue to shrink, and residents’ demand for services continues to increase, a gap between expectations and reality will grow and become insurmountable.

So both public services and residents’ expectations will have to change; public services will need to cut demand by giving away more power and responsibility to residents, and residents in turn will need to be helped to solve more of their own problems, to help themselves, and to work with the council to actively design and deliver local services.

Irreversible change

There was also a session on public service transformation with Sir Derek Myers, co-chair of the Service Transformation Challenge Panel, which published its report at the end of November. More on those recommendations on page 37.

When Sir Derek spoke at Solace, the report was still being written and he provided insight into the process the panel had gone through. The panel was trying to test for, and find the conditions for, system change of a “radical nature”, he said.

The panel came up with its own working definition of transformation: “It’s a radical new way performing a statutory duty or a core service that will involve drastically reduced costs and will likely be irreversible,” Sir Derek said.

Some of the reasons why change is needed are well-known, he explained: less money, rising demand, entrenched cost and dependency, new technology and changing expectations. However, Sir Derek said there was a sixth, less well-known driver for change: “The prevailing politics.”

He explained: “I don’t see much difference in the political offer, at least in the early part of the next Parliament. There is this expectation that the country seems to have adopted that paying down the deficit is the number one priority and that tax is still an undesirable part of an economic policy for any government.”

Public service redesign

Service design is about doing things differently; it’s about social innovation, collaboration, being visual and being people-centred. It is a relatively new discipline but most of all, we are told, it’s about championing great design to change lives.

That was the message put to a packed house in the main room on the second day of the Solace Summit. Two members of the Design Council, Helen Lazarus, head of design support programmes, and Gavin Pryke, a design associate, extolled the virtues of service redesign for public services to a rapt audience of local authority chief executives, who know that with diminishing funding and rising demand the services their authorities offer must change if they are to remain viable.

Lazarus introduced the audience to the Design Council, the government’s advisor on design, which champions creative and innovative design approaches to public services and businesses nationwide, in addition to going in and working with companies and authorities and helping them change their services for the better.

Pryke explained what service design is, and how the Design Council works with organisations to instil it. The first step, he said, is actually to take a step back: look at the whole issue, and consider the ‘real problem’. Who does it affect? What causes it?

Pryke said that often you need to redefine the question and the challenge. “It can drastically change the outcomes if you ask a better question to start off with,” he said.

Core principles

Once the question has been identified, there are three core principles – regardless of the precise organisation or nature of the challenge.

The first is being people-centred, which is easier said than done.

“People don’t create ideas in a vacuum,” he said. For example, the Design Council worked with the council in Teignbridge, Devon, to try to prevent elderly people tripping and falling at home – the kinds of accidents that usually mean a hospital admission and a rapid decline in health outcomes and life expectancy. The area has an older-than-average population, with 7% over-85.

Finding a solution meant working not just with the end users but with voluntary groups, GPs and other councils, because “solutions will have to work across those different silos”.

The second principle is being ‘visual’ – throughout the design process, not just with the outcome. He said: “Working visually makes things simpler; making things simpler aids communication; and communication, especially when you’re working across different groups that deliver services, helps innovation happen quickly and more successfully.”

The final principle is prototyping, and about being collaborative and iterative, testing ideas before implementing or piloting them. Such opportunities help negate some organisations’ natural risk-aversion.

He provided another example from Teignbridge, after work with a GP practice. “The GP surgery had a leaflet for everything: they had 874 leaflets. If there was a problem they had a leaflet. But nobody really knew anything about them and when we talked to users, there was really low awareness about the issues,” he said.

So with Pryke’s encouragement, the practice dared to try something different. “They wrapped the surgery in bubble wrap. It may sound a bit crazy, but they wanted to try it out and, sure enough, people asked what they were doing and they started having conversations with service users, raising awareness and referrals off the back of that.”

That ‘fall proof’ campaign, which ran across two surgeries with help from Sea Communications, was not seriously suggesting elderly people covered their homes in bubble-wrap, of course, but raising awareness in this way encouraged new conversations about sensible ways of avoiding falls.

“It’s these three principles, these core aspects of innovation or design, that help innovation happen and help it happen successfully. And it’s these three that we recommend and use in our work,” he said.

‘The hardest thing to change is yourself’

David McNulty, chief executive of Surrey County Council, then took to the stage to talk about the changes his authority has gone through over the last few years.

“I’m still a believer in public service and public service being able to change the world,” McNulty started as he began to take the audience through the “creation story” of Surrey council as it now exists, starting with a massive engagement campaign with several thousand staff about values. What sort of organisation did they want it to be?

“We honed in on core values and tried to construct or design the organisation that would have those values,” McNulty said.

Changing the behaviours of the organisation to exhort those values was one of the most difficult things to do, he said. “The hardest thing to do is change yourself: that’s true for individuals, its true for teams; it’s true for whatever group that you want to change. We have deep-seated drives within ourselves, deep-seated things that trigger the way we behave, and changing behaviour isn’t easy.”

Surrey has a coaching programme focused on behaviour change, which McNulty hopes to put 10,000 staff through over five years. Since it started, there has been a five percentage point improvement in how employees view their workload and supervision – at a time when staff are having to work harder and do more.

McNulty also said that as a result of the coaching, 80% of staff believe their job performance has improved, while the council has seen a massive 49% fall in sick days.

This internal success has translated externally too: there has been a 55% increase in resident perceptions that Surrey County Council employees ‘are attempting to understand their needs’.

Public value

The next step was ‘creating public value’, examining every aspect of the council and asking: where is the value sewn? “It is always in that interaction between someone who is working through us and a member of the public,” McNulty answered. So, the whole organisation needed to be turned round to support that interaction.

“A huge amount of what we do is historically based around feeding the ‘democracy beast’ of the organisation, and you actually detract from the value sewn by getting people doing all sorts of mindless things that serve the machine and not serve the public,” he explained.

The council conducted 29 internal public value reviews and as a result they are on course to deliver a saving of £279m by the end of next year.

At this point McNulty and the organisation started to look at how they could inspire change to happen more quickly.

To do this they supported a group of staff to become practitioners in RIE (Rapid Improvement Events) methodology: a mechanism to radically change current processes and activities very quickly.

‘You have until 2pm on Friday’

This group now works with other staff to do just that. The typical process starts with identifying an area that they’re not happy with, often with suggestions coming from staff themselves, and then a group of 20-25 people would be given a week where they’re put in a purposely selected space and are told to confirm what the problem is and come up with the answer. They have until 2pm Friday, when they tell McNulty and the council leader what needs to change.

“It’s been incredibly successful in terms of energising staff and coming up with some really great ideas and very important changes,” McNulty said.

The organisation has conducted 17 RIEs so far, with McNulty being most proud of one which resulted in simplifying and reducing the amount of processing time the organisation spends on social care assessments, cutting bureaucracy for frontline social workers.

That approach has more recently been adopted in the council’s collaborations with other agencies and partners.

“We rely on others to work with us to achieve the outcomes we want. And therefore we started thinking through, how is it that we could build co-design, local delivery and whole systems approaches into what we were doing.”

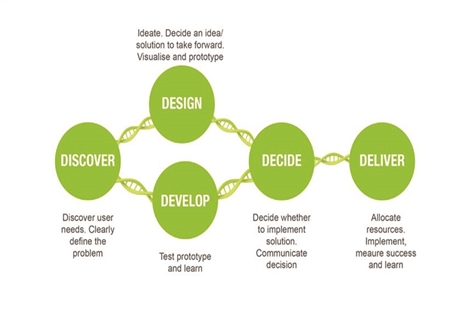

To achieve this, they established an approach similar to that of the Design Council. They start with a discovery phase, where they try to clearly define the problem. Next they move onto idea generation, and start thinking about how this might be solvable.

Then the project moves through a prototyping and testing loop, until there is sufficient evidence for a business case. Once that is achieved, “you take the business case and throw all the resources of the organisation behind it to deliver it”.

McNulty said they don’t expect any one person to be good at all phases of the process. “We get away from the idea that one person starts and finishes, or one team. We bring in different people because different people are better at different elements of this. Some people are absolutely fantastic at delivery but not so great with coming up with new ideas. Some people are brilliant at coming up with ideas but have never delivered anything in their lives. The trick is to put those people and the sequence of work together in a way that they actually add value to each other.”

Dual operating system

Having already achieved so much, McNulty has not lost ambition – he is anticipating future challenges.

He believes the next step will be finding a way for authorities to master John Kotter’s idea of the ‘dual operating system’, where a bureaucracy can work in the strict hierarchy that is required for delivering services, while also having another, more agile ‘operating system’ alongside it allowing innovation and creativity.

Some organisations use two different groups of people to achieve this, but he doesn’t see that as sensible for councils. “We want people who can be equally comfortable moving between both domains but to be conscious when they’re moving from one to the other. So, to me, getting that right will be the key challenge for all public services over the next two to three years.”

Tell us what you think – have your say below or email [email protected]