The high street was undergoing a transformation before the coronavirus hit. And then came the lockdowns...

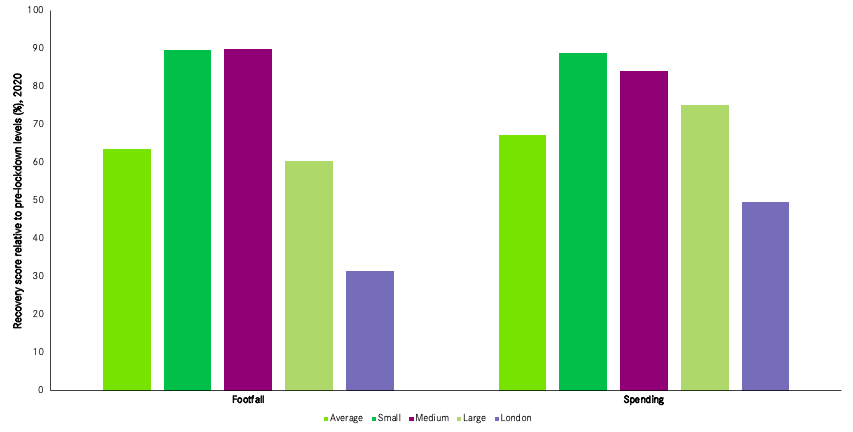

Using mobile phone and card sales data Centre for Cities has been monitoring how city centres across the country have been recovering economically from Covid-19. Data from our tracker shows that as of the end of August, footfall was back up to 63 per cent of its pre-lockdown level and spending was slightly ahead, at 67 per cent. This, of course, isn’t the same everywhere.

Large cities are recovering slower than the smaller places

The larger the city, the slower it seems to be recovering. London is barely back up to a third of its pre-lockdown footfall and half the spending. Manchester and Birmingham are faring better but still lagging behind other places, with footfall at around half of pre-lockdown levels.

Smaller cities and large towns are recovering more quickly. 14 of the cities studied have recovered past pre-lockdown footfall and 12 are seeing higher spending than before. All of them small or medium in size.

Figure 1: Footfall and Spending recovery, by city size

Source: Locomizer (2020), Beauclair (2020)

Pre-lockdown dominance of offices and reliance on public transport driving these trends

There are several factors to note here. First, the centres of large cities tend to have less residential and industrial space and denser concentrations of office jobs which are now being done from home. This limits how many workers are in these city centres compared to before.

People in cities, especially London, are also more reliant on public transport than their counterparts in other places. With public transport capacity still greatly reduced, it is now harder for people to travel into the centres of large cities.

Local centres in Greater Manchester are recovering faster than the city centre

In addition to a city-by-city analysis, we have also looked in detail at the recovery of footfall in Greater Manchester to gain a better understanding of how large city-regions are recovering. We compared eight local town centres in Greater Manchester with Manchester city centre and found that footfall in all of these local centres is recovering faster than in the centre.

Figure 2: Overall recovery up until the end of August

|

Local centre/City |

Latest full week (% of pre-lockdown levels) |

|

Wigan |

102 |

|

Ashton under Lyne |

77 |

|

Bury |

75 |

|

Rochdale |

73 |

|

Bolton |

66 |

|

Stockport |

64 |

|

Altrincham |

62 |

|

Oldham |

61 |

|

Manchester |

49 |

Source: Locomizer (2020)

But not all local centres are recovering equally. Altrincham and Stockport, areas with more of their residents working in Manchester city centre, are recovering more slowly than Rochdale and Bury – places with smaller shares of residents working in Manchester city centre. This suggests that the working from home boost to the local economy that some commentators have predicted does not seem to have materialised in the local centres of Greater Manchester.

The road to recovery has so far been bumpy and uneven

Recovery is not happening at the same pace everywhere. Footfall dropped earlier in London and other large cities. When it did, it fell much further and picked back up later and more slowly than small and medium-sized cities.

Places also benefited from Eat Out To Help Out to different extents. In the vast majority of places, sales rose more than footfall, with average sales on Mondays to Wednesdays rising by 49 per cent. Sales increased most in Leicester, which came out of lockdown just as the scheme was starting. Leicester was followed by Newport, Swansea and Cardiff. Sales actually fell in Aberdeen, owing to a local lockdown.

Regardless of Eat Out to Help Out, lockdowns and local restrictions have had a strong impact on city centre recovery, but the degree to which a local lockdown hits business depends on several factors, including whether it targets at-home mixing over pubs and restaurants and the degree to which a place recovered from the first lockdown.

While footfall in some city centres exceeds pre-lockdown levels. it is worth bearing in mind that we are comparing the summer holidays to three wet weeks in February. Additionally, although it is encouraging that some places are now back to ‘normal’, this does not mean their local economies are saved. In Wigan for instance, where footfall now exceeds pre-lockdown levels, one in five shops are vacant and the area still has serious underlying economic problems that should be addressed.

The economic impact of Covid-19 is not the same across the country. So far guidance and solutions have been led from the centre, this is understandable. However, as we enter a new more localised phase of the crisis, the support offered to places should be tailored to suit their needs and local authorities should be given the powers, tools and resources to respond to their local needs as they see fit.

Lahari Ramuni is a Researcher at Centre for Cities. You can explore their High Streets Recovery Tracker here.