02.01.19

No end to austerity for local government

Source: PSE Dec/Jan 2019

Dr Mia Gray and Dr Anna Barford, both of the University of Cambridge, argue that the ghost of austerity continues to haunt the local government landscape as many councils struggle to offset often profound budget cuts – especially across England.

On 2 October, in the prime minister’s speech to the Conservative Party Conference, Theresa May heralded the end of austerity. She said that “after a decade of austerity, people need to know that their hard work has paid off.” Speaking in the past tense, May asserted: “Public sector workers had their wages frozen. Local services had to do more with less. And families felt the squeeze. Fixing our finances was necessary. There must be no return to the uncontrolled borrowing of the past. No undoing all the progress of the last eight years. No taking Britain back to square one. But the British people need to know that the end is in sight. And our message to them must be this: we get it.”

After this announcement, the chancellor’s spending plans were somewhat watered down, as he phrased it as “austerity is coming to an end” rather than being over. Of course, semantics aside, his spending plans, while offering a boost to social care spending, have not fundamentally altered austerity – and particularly not altered it for local government.

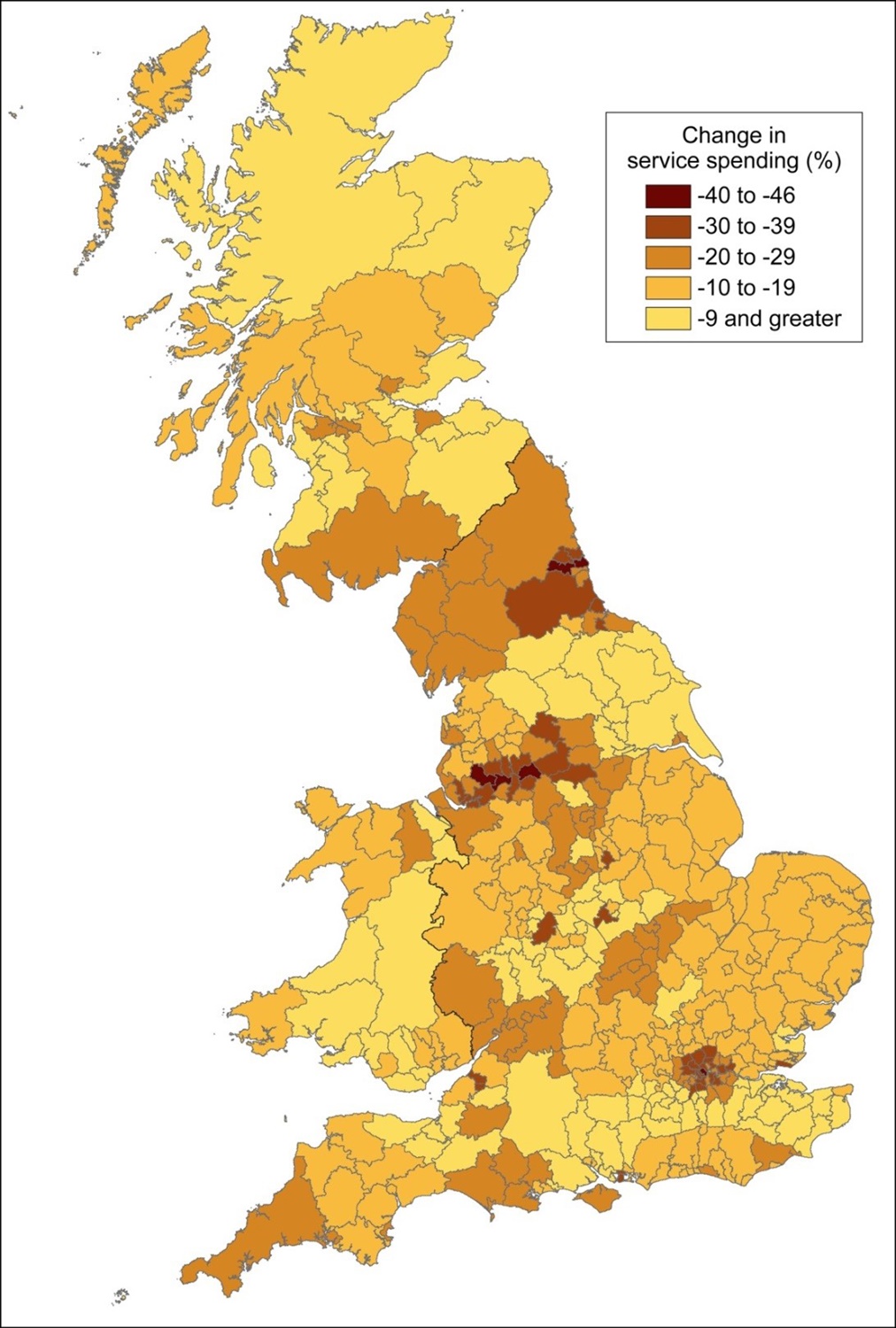

Our research on local government spending cuts in the UK offers a chance for local authorities to compare their position to others in the country. We used data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, calculated to enable comparisons between different local authority areas, and removed spending on the services which have changed so dramatically that comparison over this time period is impossible. We can see that while the cuts in the central government grant are proportional across the country, actual cuts to service spending vary enormously (Figure 1).

The map shows that although the central government’s funding cuts to local government are the major driver of reductions in spending on local government services, the actual spending cuts made by local government in 2009-10 to 2016-17 range from 46% to a mere 1.6%.

However, because the importance of the central government grant as a proportion of the total local government budget varies by such a large percentage, across-the-board austerity cuts in council spending have fallen most heavily on those local areas with the greatest need. This is only exacerbated by differences in the ability to raise revenue locally – through taxation and fees, the size of reserves, and the value of prime land and buildings.

Despite the fact that some local governments have more ability to manoeuvre around cuts in central government grants, there remains a notable relationship between grant dependence and the cuts in local service spending – the larger the proportion of the local government’s budget is derived from the central government grant, the bigger the spending reductions. Those areas where a greater proportion of the budget came as a grant often have comparatively limited possibilities for raising revenue by other means, and a high level of need for services amongst residents. This means that cuts to central government grants often translate into cuts in service spending, as many local governments cannot, or can only partially, buffer against the cuts – especially given recent caps on local tax increases.

It will not come as a surprise to many that discretionary services have suffered the largest cuts, in areas such as planning, housing, and highways and transport. Discretionary funding includes many public goods – amenities such as libraries and parks – and spending cuts on these services have been severe. For example, 343 libraries have been closed down in the UK between 2010 and 2015, with a loss of over 5,700 professional staff in the same period. Of course, with over 1,100 statutory spending requirements, the boundary between mandatory and discretionary spending is not always clear.

Mandatory and discretionary spending often co-exist in the same budget and support similar goals. Support and preventative services are often the targets of cuts, and while not mandatory, they can be fundamentally linked to the goals of the mandatory services. For example, youth centres, a discretionary support service for low-income youth across the UK, have been severely cut and are often not considered part of the mandatory package for children who are ‘at risk,’ even though the youth centres directly target many at-risk children.

Additionally, although mandatory services are relatively protected, the scale and quality of the public service is not. Many aspects of welfare for vulnerable and ageing adults and services for children in care have suffered a budget decline in real terms, decreased in quality, and raised eligibility thresholds for service users. For example, demand for children’s services increased between 2010 and 2017 in the form of 13% more children in care, 31% more children with a child protection plan, and 108% more referrals to social care services – leaving budgets for young people’s services reduced in real terms by £2.4bn between 2010-11 and 2015-16. At the same time, the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government passed on £1.6bn to its own children’s services spending, which contributed to a small increase of 3.2% in real-terms spending by local government on children’s services from 2010-11 to 2016-17. However, this small increase was not enough to offset the large upsurges in demand and, thus, spending per child declined in the same period.

Children’s services are very illustrative of the larger issues. Many of these service cuts are difficult to reverse – it is often more difficult to build an effective organisation than to dismantle it. Trust and social networks, which are fundamental to their functioning, are easily diffused. Expertise goes elsewhere. Knowledgeable, professional staff retire and are replaced with younger staff members with less ability to effectively navigate the system.

Even if there were more funding from the chancellor, it will take time and energy to rebuild this type of social infrastructure. Clearly, for local government, the legacy of austerity will be with us for some time.

Top image: NurPhoto via PA

Enjoying PSE? Subscribe here to receive our weekly news updates or click here to receive a copy of the magazine!