14.07.17

Poorest communities live in good health for 20 years less than rich counterparts

A ‘groundbreaking’ report has today been released by Public Health England (PHE) detailing the health profile of England, finding that people in the most deprived areas had the lowest life expectancy on average.

PHE revealed that males in the most deprived tenth of areas can expect to live nine fewer years compared to those in the least deprived. For women, the difference was seven years.

More shockingly, men and women in less deprived areas can expect to spend nearly 20 fewer years of their life in good health compared to richer people.

Reasons for this difference were put down to higher rates of smoking in poorer areas, as well as higher amounts of obesity.

The report aimed to “tell a story” about England’s population by collating data about tobacco use, the National Child Measurement Programme and other information to draw up the detailed report.

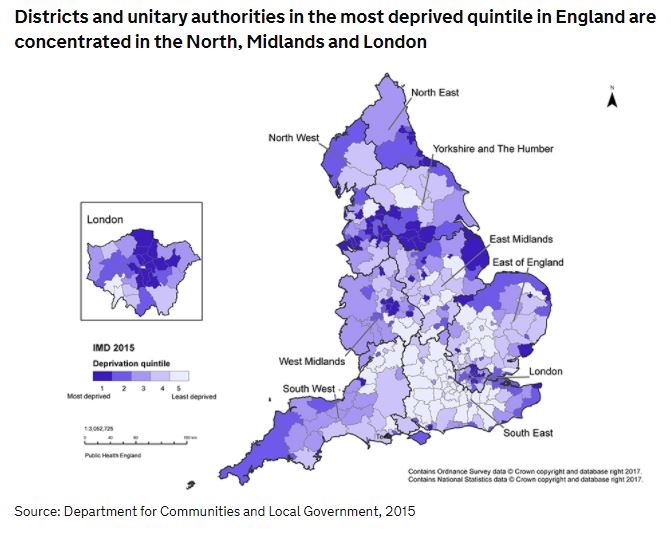

The organisation’s report also found a considerable divide between the north and south, saying that a number of deprived communities were concentrated in the north of the country, although a number of poorer communities were also concentrated around North London too.

PHE also discovered that women live three years more of their life in poor health than men do. Men were found to live 16.1 years in poor health, whilst for women the figure stood at 19 years.

It also found that dementia and Alzheimer’s have overtaken heart disease as the most common cause of death in the country, increasing by 60% with males and doubling with females.

The report also comes in the same week that local councils slammed central government for a “short-term approach” to public health spending which had led to certain problems being exacerbated in many areas.

Cllr Izzi Seccombe, chair of the LGA’s Community Wellbeing Board, said: “This groundbreaking PHE analysis shows how deprivation can lead to long-term ill health and premature death for the most deprived.”

The LGA lead added that the findings demonstrated something the LGA was aware of, that those living in the most deprived communities experience poorer mental health, higher rates of smoking and greater levels of obesity than the more affluent.

“They spend more years in ill health and they die sooner,” she added. “Reducing health inequalities is an economic and social challenge as well as a moral one.”

Cllr Seccombe went on to say that local authorities and their public health teams understand how to use their traditional functions in conjunction with their newly acquired public health expertise to maximise the role councils can play in closing the unjust health inequalities gap.

“But reductions in councils' public health grants of more than £530m by the end of the decade will impact on councils’ ability to continue this good work,” she explained. “Central government has to play its part in reducing poverty and breaking the link between deprivation, ill health and lower life expectancy.”

Have you got a story to tell? Would you like to become a PSE columnist? If so, click here.