06.01.17

Lessons from Germany to fix the UK’s housing crisis

Source: PSE Dec/Jan 17

Dr Charlotte Snelling, a researcher at IPPR, and Ed Turner, senior lecturer and head of politics and international relations at Aston University, look at the lessons the UK can learn from Germany in tackling the country’s housing crisis.

The UK faces significant challenges in providing sufficient housing, at a price people can afford. The housing shortage is pricing people out of their local communities, fuelling inequality and reducing labour mobility.

It may not be fashionable, in the months after the UK’s decision to leave the EU, to suggest we turn to continental Europe for inspiration on how to solve domestic problems, but our new research finds there are valuable lessons to be found in Germany.

In both Germany and the UK, housing is a growing political issue. It dominated the 2016 London mayoral election campaign, and it was equally prominent in Berlin’s recent state election. Long-standing residents find themselves being priced out of the city that they call home.

On the face of it, Germany’s record is stronger than that of the UK. It has consistently outperformed the UK in supply, building 30 million homes since 1951 – nearly double the rate of the UK. In recent years, it has achieved over 250,000 completions annually, again comfortably exceeding the UK’s output of 170,000 in 2015, which was the highest number of homes built in a year since the crash.

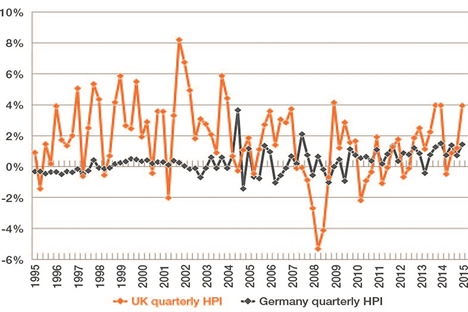

House prices, in part as a result, are also far more stable (see chart).

So, how have the Germans done it? First, Germany relies far less on the market to solve its housing supply problems. For example, its local authorities have powers to declare “urban development measures” where sites are not being developed – a common problem in the UK. They assemble land (paying owners what it is worth in its current state), arrange housing construction, and use the difference in money paid, and money received, to finance infrastructure.

Secondly, whereas in England the small and medium-sized (SME) building sector imploded in the 1980s and never recovered, in Germany there is far greater diversity, with most houses built by locally or regionally-based firms, and complemented by housing associations and public housing companies. The large upfront financial investment in preparing planning applications with uncertain outcomes has long been a complaint of UK SME builders, presenting a huge barrier to entry. German planning processes offer greater certainty to would-be housebuilders earlier on. When land is earmarked for development, provided particular tests are met, the final planning permission is likely to be granted. This brings benefits for communities, too, by allowing early consultation and meaningful input into land use allocation.

Thirdly, although home ownership remains an aspiration for many Germans (especially in rural areas), the fixation with this is less apparent than in England, and public support for rented housing is stronger. This is not unrelated to the fact that renting in Germany is, for established tenants, characterised by stable rents and security of tenure.

Finally, Germany has a more conservative mortgage market than the UK, which keeps a lid on house price booms, reduces exposure to financial crises, and means that those looking for a home are more likely to see renting as a desirable alternative to buying.

Of course, Germany’s housing policy isn’t perfect. Significant strains have emerged as a result of an erosion of social housing (from 3.9 million social units in 1987 to just 1.5 million in 2013), a consequence of privatisations but also previous legal requirements to retain the ‘social’ rent of a flat only for 20 to 30 years. Rents have spiralled in booming urban centres like Munich, Frankfurt and Berlin, and politicians of all stripes express determination to address this issue.

Our point here is not that the UK should replicate all aspects of Germany’s housing policy – trying to implant the German market wholesale onto British soil would be a futile undertaking; there are practical, economic and cultural reasons why that would not work. However, we can clearly learn lessons from a country that seems to be finding sound answers to challenges we continue to be stumped by here in the UK.

With ministers about to publish a housing white paper, the government would do well to learn from the German approach to land assembly, the role of SME builders in the German market, and why the country is so much more successful in turning planning permissions into homes.

House prices in UK and Germany, 1995–2015 (quarterly % change). Source: Bank for International Settlements, BIS Residential Property Price database (BIS 2016).

For more information

W: www.ippr.org/publications/german-model-homes

Tell us what you think – have your say below or email [email protected]