30.09.15

First-ever net fall in care sector beds as public investment ‘dries up’

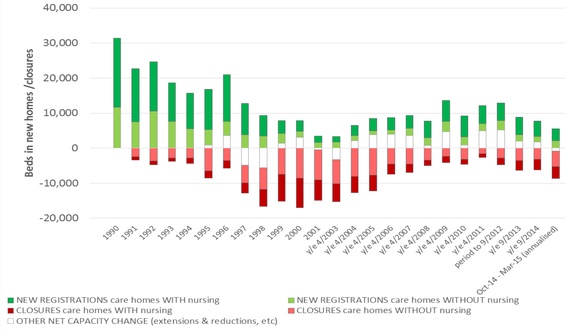

Investment in new capacity in the publicly-funded care sector has “largely dried up”, with the first-ever net fall in beds.

Between October 2014 and March 2015, 3,000 more beds in the elderly care sector ‘closed’ than ‘opened’.

The research, led by healthcare analysts LaingBuisson, also found that private providers were bringing in “healthy” profits (25-30% of their revenue), while the public care sector’s profit hovers around the “worryingly low” 15% mark – with the potential of slumping to 10% after the introduction of a national living wage.

Low investment levels in new public care sector capacity were mostly due to “pressure on fee margins”.

Click on the image to enlarge it.

Click on the image to enlarge it.

LaingBuisson’s CEO, William Laing, said “the big question” for local authority care commissioners and care company executives now is whether Whitehall will “bail out” providers facing the threat of “going underwater” in the upcoming Spending Review.

According to the report, ‘Care of Older People’, there were two “game changers” in the care sector: delaying the second phase of the Care Act and the announcement of a national living wage.

The former was a positive announcement as measures included in the Act were “set to expose care home operators to further major financial risks”.

But the introduction of the NLW “swapped one major challenge for another”. The organisation’s report claimed that estimated additional costs expected to come in as a result of the living wage will equate to around 4% in care home operating profits as a percentage of revenue, “unless mitigated by higher fees”.

However councils lack the private provider capacity to pay higher fees to “prop up” extra costs without further funding injection from the government.

The report said: “As such, ‘public pay’ care home companies face the prospect of operating profits falling to a dangerously low level of around 10%, where even those with modest levels of gearing could face financial failure.”

Laing added: “The care home market is subject to a self-righting mechanism like any other market. Investment is curtailed when prices (as now) are insufficient to offer a reasonable return in areas of high public pay. As a result, against a background of rising demand, shortages can be expected to appear. Market power will shift towards providers, prices will rise and public authorities will be forced to find extra resources.”

He said the company’s prediction for the Spending Review was that some new funding would be made available to councils to help the care market “withstand the shock” of implementing the NLW.

“Nonetheless, whatever new money is injected, it will in all probability be insufficient to re-establish the margins of care home operators with high exposure to public pay at the level they were prior to the 6% real terms reduction in councils’ baseline fee rates since the beginning of public sector austerity in 2011-12.

“Therefore, the ‘capacity shortage’ scenario as described will in a probability continue to be played out a variable pace in about 200 council areas before some sort of national equilibrium is restored, possibly before 2020.”

The research was conducted using figures derived from CQC data and from other national regulatory bodies.

Earlier this month, the National Care Association warned that the "chronic underfunding" of social care by councils could drive 24% of care providers out of the market and worsen the bed shortage crisis by 40,000 places.

This could in turn lead to an “exodus” of providers, driving thousands of “frail older people” into the NHS – which would result in hospital admissions for non-acute conditions.

The association had blamed the underfunding and the upcoming introduction of the living wage in April for “seriously eroding the viability of many care home businesses”.