17.11.14

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards: applications and costs spiral

Some council social care departments have had five times as many Deprivation of Liberty Safeguard (DoLS) applications in the first half of this year as in the entirety of 2013-14. This is putting significant strain on councils, both in terms of manpower and money. David Stevenson reports.

During the first quarter of this financial year, figures from the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) revealed that DoLS applications to the social services department at Dorset County Council (Dorset CC) increased to 1,176 compared to 228 in the whole of the previous year.

The local authority granted 167 applications, declined 242 and the remaining 767, for the most part, were ‘pending’ action. This was mainly because the local authority – as is the case for many across England – does not have enough trained, full-time DoLS assessors.

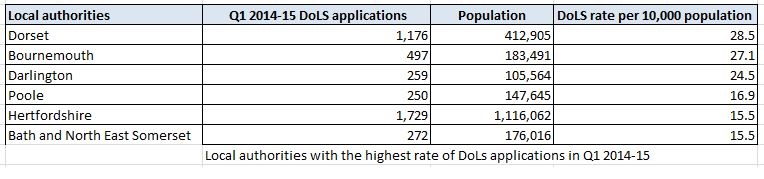

Although Dorset CC didn’t receive the highest number of DoLS applications in absolute terms – this went to Hertfordshire with 1,729, up from 261 the previous year – it had the highest rate of applications per 10,000 population, at 28.5.

By using the latest census data and HSCIC’s figures, PSE found a major variance in the rate of applications across the 130 local authorities that submitted DoLS data in Q1.

Dorset CC had the highest rate followed by Bournemouth (27), Darlington (24.5) and Poole (16.9). The local authority with the lowest application rate, among those that supplied figures above zero, was Hammersmith and Fulham with 0.8 applications per 10,000 population.

Paul Greening, Mental Capacity Act manager at Dorset CC, told us: “Demographics have a part to play in this. We have a significantly older population in our area and the largest proportion of applications is for those suffering from dementia.

“We’re doing five times as many assessments this year as we were doing last year. Despite doing five times as many the waiting list is getting longer. The more assessors you have the more assessments you can do. But at the moment we don’t have a full-time best interest assessor (BIA) – ours have other jobs but as part of that they do DoLS assessments.

“Dorset CC has agreed to pay overtime to staff, particularly to part-time staff, to do assessments in their days off to maximise the number of assessments we can do. We’re also using private BIAs far more than we ever did.”

The changing DoLS landscape

DoLS form part of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, and are aimed at ensuring people in care homes, hospitals and supported living are looked after in a way that does not ‘inappropriately’ restrict their freedom.

It has been recommended that those planning care should always consider all the possible options prior to making an application before depriving a person of their liberty.

In March, the Supreme Court ruled, as part of the Cheshire West cases, that to determine whether a person is objectively deprived of their liberty there are two key questions to ask, which they describe as the ‘acid test’:

- Is the person subject to continuous supervision and control?

- Is the person free to leave? (The person may not be saying this or acting on it but the issue is about how staff would react if the person did try to leave).

This now means that if a person is subject both to continuous supervision and control and is not free to leave, they are ‘deprived of their liberty’.

According to the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS), the judgment is significant in determining whether arrangements made for the care and/or treatment of an individual lacking capacity to consent to those arrangements amount to a deprivation of liberty.

In short, the Supreme Court ruling means every individual is entitled to their own assessment rather than a general one.

But there are also a number of implications for local authorities as a result of this judgement. For instance, there was always likely to be an increased number of applications for DoLS authorisations (both ‘Urgent’ and ‘Standard’), which has inevitably placed pressure on local authority DoLS teams and on the capacity of BIAs.

There was also likely to be a need to revisit previous decision making and address them in some cases. There has also been a greater need for the dissemination of factual and helpful material to assist managing authorities and other partners to identify when applications are needed.

David Pearson, president of ADASS, said: “The first concern is that people who do not have capacity to make important decisions, or who are not free to leave a hospital, residential home or a domestic setting, receive proper consideration of what is in their best interests.

“We are also keen to ensure that their needs are met in a timely manner and that any process should not cause any undue delay as well as complying with the law. Clearly the judgement by the Supreme Court has clarified that a far greater member of people require an assessment and this has a significant additional extra cost.”

Since DoLS apply only in hospitals and care homes, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) noted that it is certain that many more applications will be made to the Court of Protection for those in domestic settings with support.

Phillipa Bruce-Kerr, a partner at law firm Harrison Clark Rickerbys, said: “This is placing a burden on the local authority legal teams, and some practitioners suggest that this is in turn impacting on the willingness of the local authorities to undertake other legal actions in the context of their Welfare and Safeguarding obligations as limited resources can only go so far.”

Frontline action

Speaking about what affect this has had for Dorset CC, Greening told us that the team sent out information to all the care homes and hospitals that the judgement had happened and passed on information from the DH and the local authority about what they thought it meant for people who ‘lacked capacity’ and were under continuous supervision and control and were not free to leave.

“We were also encouraging them to make referrals where they felt it was appropriate and there weren’t ways of reducing the restrictions or caring for people in a different way that avoided a deprivation of liberty. To be honest, I think that is much more difficult to do now,” he told us.

Greening noted that extra funds have been made available through the council to deal with DoLS applications – even though these are not times when there is money floating around local authorities. “But, ultimately, the pressure it puts on the local authority is immense and without additional resources from somewhere that is going to have an impact,” he said.

‘Little time to adjust to this additional burden’

Another local authority that has seen a spike in its DoLS applications is Poole Borough Council. During Q1 of 2014-15, the local authority saw the number of applications increase to 250 up from 88 in the previous year.

David Vitty, head of adult social care at the unitary authority, told us: “We’ve experienced a major increase since the Supreme Court ruling and we’ve had very little time to adjust to this additional burden.

“What we’ve had to do is, to some extent, restructure our staffing to and bring in practitioners from fieldwork teams directly into DoLS assessment and at the same time we have had to train more qualified staff as BIAs.”

Best interest

BIAs play a crucial role in DoLS cases in determining whether a person has or will be deprived of their liberty and whether this would be in their best interests.

In England, most BIAs are social workers who have to do a qualification course at a university and then refresher training every 12 months, which can be with a university or training company.

At both Dorset CC and Poole, more people are going through training and the councils want to do even more training in the future. However, despite training more BIAs, both councils added that there has ‘inevitably’ been a backlog in dealing with DoLS applications.

Greening noted that the increase in applications and the need to train more people is putting “significant strain” across the board, but it isn’t just within his team.

He added that one of the difficulties is that BIAs, who tend to be the most experienced and capable members of staff, often have other roles and responsibilities. “Removing them from their other posts to say all our assessors need to just do DoLS assessments would be fine, from a DoLS point of view, but the rest of the system falls apart,” said Greening.

“All of social and health care are under pressure at the moment. But this is a statutory duty, it is an important safeguard for people who’re potentially vulnerable, it needs doing and it is how we find the best resources, time and bodies.”

During Q1 of 2014-15, Poole received 250 DoLS applications. It granted 185, declined 8, but had 57 which were still in the pipeline.

Vitty noted that in order for a ‘quality assessment’ of a DoLS application to be carried out it would be at least half a day’s work to assess the individual and another half to write it up.

“So, it is a full day’s work for a qualified professional to complete one assessment,” he said. “Currently, we don’t manage to undertake the assessments as quickly as we used to, so it is not unusual now for requests for DoLS authorisations to wait longer.

“This is an important statutory process and it is not something we can do with any less rigour than we used to. There have been a few national measures that we welcome. For instance, the Court of Protection is looking at simplifying the process and ADASS are working with councils to develop a new set of forms that we hope will be shorter and more straightforward to complete.”

Last resort

Applications to restrict the freedom of people with illnesses, such as dementia and autism, should only be made as a last resort, according to the Alzheimer’s Society.

George McNamara, head of policy and public affairs at the dementia charity, told PSE: “DoLS shouldn’t be an easy route for care providers. What’s most worrying is the lack of awareness and understanding about the use of DoLS and safeguards across these bodies and organisations.

“We know, for example, that over half of the applications were for someone with dementia – so much more needs to be done across health and social care to make sure these safeguards are better understood and recognising when it’s appropriate to be used. But also we need to recognise what the alternatives are and how, for example, investment and the delivery of person-centred care can actually in many cases, but not all, reduce the need for these applications.”

In response, Vitty noted that the local authority has a duty to advise care providers about the Supreme Court ruling as the supervisory body. “So, with our neighbouring councils, we have written to providers,” he said. “We felt it was important to let them know that they have this duty to seek authorisation when they think they’re depriving someone of their liberty.”

He also noted that the local authority has to make financial provision for next year and beyond because each DoLS assessment requires a doctor to be present, for which there are fees. So the already stretched budget also has to make provision to pay for medical colleagues to take part in the assessments.

“We also need to make financial provision for additional staff. As well as making interim arrangements to move staff around the organisation we are going to need some growth money to manage this in the long term,” concluded Vitty.

McNamara told us that money is tight in all areas, but this is more about ‘priorities’. The charity’s spokesperson noted the positive role that raising DoLS awareness, through existing forums and committees, can have.

When asked whether greater financial support from the DH would be useful, he said: “It would help but it is limited; I would say the best support is more about information. Where I think an active role could be played is from the CQC when they do their inspections.”

The CQC, in its guidance to care providers, noted that care plans for people lacking mental capacity need to show evidence of best interest decision-making in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act, based on decision-specific capacity assessments.

“In particular, providers should ensure that restrictions on the freedom of anyone lacking capacity to consent to them are proportionate to the risk and seriousness of harm to that person, and that no less restrictive option can be identified,” the regulator noted.

Barbara O’Brien, lead manager for statutory mental health, including DoLS, at Poole, told us that registered care providers are being challenged by the CQC, quite rightly, as to why, if they haven’t made applications. “You’ve got a multi-pronged approach with the local authority saying you need to ask us, plus you’ve got CQC saying that you cannot just deprive someone of their liberty,” she said.

Asked whether local authorities are likely to see a plateau-effect occur with regards to DoLS applications, O’Brien was not convinced this would happen. This was despite DoLS applications in Q2 at Poole and Dorset CC, and in a number of other councils, falling slightly compared to the Q1 figures.

“In Poole we have an acute mental health hospital and a significant number of registered care homes, and care homes with nursing care: that’s not going to change,” said O’Brien.

“We will also find ourselves in a position in April where we need to review people that are coming up for a review [DoLS authorisations can be for up to 12 months] and whether they still need to be authorised and deprived of their liberty. I can’t see it easing off just yet.

“On a positive note, as local authorities, we’ll be looking at our assessments. So prior to somebody going into a care home, if you look at what the Care Act is telling us, we should be looking to see if we’re going to be potentially depriving someone of their liberty so it will help people to look at different alternatives, perhaps. And therefore we’ll be able to manage it that way.”

Dorset CC’s Greening added that going forward the robustness of the DoLS authorisation system must remain in place. “If it turned into a tick-box mentality we all might as well go home, if it doesn’t remain a proper safeguard,” he said. “We have had discussions with our BIAs about ways to speed up and streamline the system for everybody, but there is a limit to that.”

Looking at the Q1 figures for the 130 local authorities surveyed by HSCIC, it was revealed that during this period 21,563 DoLS applications were made, up 73.7% from the 12,414 applications made in the entirety of the previous year. ADASS has written to the government outlining the impact and concerns it has with regards to the sharp increase in DoLS applications.

In fact, the organisation has led a Task Group at the government’s request to ensure that this is being done as effectively as possible.

ADASS president David Pearson said: “But we have pointed out to the government that an urgent change in the law and more resources (£88m is required) are needed to ensure that this new work is funded: this at a time when social care has had to make 26% savings over four years.”

It has also been suggested that, given the sudden scale of the increase, there is a “vital” need to recruit and train more staff otherwise the delays that are very regrettable will continue to be inevitable.

Thus far the government has not agreed to ADASS proposals for action on the change of the law but has referred it to the Law Commission for what is likely to be a lengthy review.

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK: [email protected]