22.12.16

Public service reform in the Thatcher, Blair and Cameron eras

Source: PSE Dec/Jan 17

Chris Painter, Emeritus Professor of public policy and management at Birmingham City University, assesses the impact of the public service reform paradigm that dominated the period from 1979 to 2016.

At the turn of another turbulent year – with the new May premiership still finding its bearings – this is an opportune time to reassess the impact of public service reform since the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, which proved such a critical juncture. Pre-occupation during the 1960s/1970s had been with the configuration of Whitehall departments, calibre of Civil Service advice because of the cult of the generalist all-rounder and local government structures. The Thatcher Conservative governments of the 1980s, rejecting the post-1945 political consensus, instead established a new paradigm for public service reform.

Successive waves of reform followed when Blair and Cameron were ascendant political figures. Motivated by a desire to achieve better value for money and improve service quality, the purposes of reform remained fairly constant. What has varied is the means adopted to achieve those ends. Changing nuances were often more apparent within the same premiership than between different administrations. A fundamental question remains. What is to show for decades of reform hyper-activity?

The Thatcher legacy: Laying foundation stones

Shielded from market forces, it was a self-evident truth to the ‘new right’ in the 1980s that public services were inefficient and unresponsive. New incentive structures were required to avoid public spending becoming a bottomless pit and for performance standards to meet the rising expectations of clients/customers.

So began the fixation with performance indicators and league tables, with all their attendant dangers – data manipulation and a tick-box mentality. Gone was the idea of professional trust and self-regulation, or even constructive dialogue with the so-called ‘street-level’ bureaucrats. Even better if the business disciplines of the private sector could be simulated in the form of internal service markets within the NHS and elsewhere; and better still if the real deal were achieved through opening public service contracts to alternative providers (where full privatisation presented technical or political difficulties). Some of these new providers were to leave much to be desired, G4S an obvious case in point.

Another holy grail consistent with this market philosophy was user choice, not least for parents deciding on which schools to send their children. It posited a degree of rationality and social fairness not borne out by behavioural evidence. Choices are distorted by information processing skills and the economic and social capital conferring advantages in public service markets on the more affluent and articulate.

Nonetheless, this paradigm gained powerful hold on the political community. If all else failed, an underperforming public service provider could be put into special measures or placed under new management.

New Labour: Don’t begin as you mean to carry on!

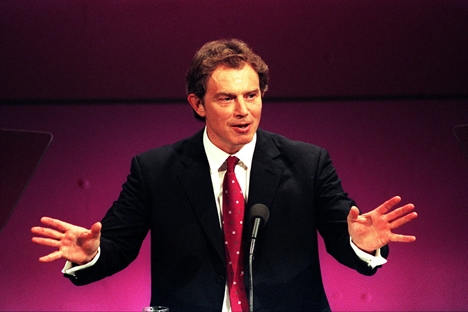

One fascinating aspect of the public service reform story is how the emphasis evolved under the same political regime. That was exemplified by Tony Blair’s experience in office from 1997 to 2007.

Initially, as prime minister, he was fully signed up to a top-down model, micro-managing frontline services from Whitehall. This led to a proliferation of national targets. Recording and reporting requirements grew exponentially, distracting public service staff from frontline responsibilities.

Blair himself eventually became sceptical that central government had effective-enough levers to add much value to local service delivery. He therefore increasingly embraced the diversity and choice agenda, so that the main drivers of performance improvement would be the threat of alternative providers and customer pressure (a philosophy earlier encapsulated in John Major’s Citizen’s Charter initiative as prime minister in 1991). Through these channels, bottom-up incentives would generate ‘self-improving’ services.

The question though – given New Labour’s fundamental mindset – was whether it could really let go, especially when Gordon Brown succeeded Blair as prime minister, with his strong belief in the efficacy of centralist administrative action.

The Coalition: All the Queen’s horses and all the Queen’s men...

Picking up where Tony Blair left off, for many ministers in David Cameron’s post-2010 Coalition government public service reform was essentially a matter of letting a thousand flowers bloom; albeit against a backdrop of austerity-driven spending retrenchment in pursuit of an ever-receding budget surplus, cumulatively affecting organisational capacity to hit performance targets – notably in the NHS.

Local authority educational responsibilities were broken up by accelerating the autonomous school academy programme initiated under Blair. Local clinical commissioning groups were established in the NHS. Moreover, opening public services to competing providers would now become the rule rather than the exception. Historical and contemporary cases of poor standards were shamelessly exploited to reinforce arguments for accelerating the pace of reform.

There were still traces of this approach after Cameron’s success in the 2015 general election. Michael Gove, in his newly-incarnated ministerial role as justice secretary, seemed intent on applying the autonomous school academy model elsewhere. Prison governors were to be granted more freedom and held accountable through league tables based on a range of performance measures (reforms paused by his successor, Liz Truss, but then revived as part of her prison safety and reform white paper published in November 2016, along with inevitable powers to intervene in ‘failing’ institutions).

Continuing deregulation of the English university sector, courtesy of the Higher Education and Research Bill, will lower barriers to entry from competitive private providers. It will also allow variable tuition fees, conditional on evaluation of performance through a new teaching excellence framework. This followed earlier removal of the cap on student numbers.

Yet by the time of Cameron’s departure from office in July 2016, a parallel trend could be discerned, putting back together fragmented pieces. Multi-academy chains rather than single school academies were rapidly becoming an expectation. Area reviews of further education colleges encouraged rationalisation through mergers, or at least closer local collaboration, so maintaining institutional viability in more stringent budgetary circumstances.

Nowhere was this process more evident than in planned reconfiguration of local health delivery systems to promote joined-up services and relieve huge pressures on NHS budgets. Hence the sustainability and transformation plans (STPs), 44 ‘footprints’ into which the country has been sub-divided by NHS England, bringing together all the statutory bodies involved in health and social care. As PSE itself discovered, however, some local authority leaders felt that their level of involvement in STPs left much to be desired. There is a risk, moreover, that resources earmarked for this purpose will be diverted in desperate short-term attempts to keep the service financially afloat in the face of ever-growing demands.

Successive governments have embarked upon their own learning curves, rather than capitalising on longer institutional memory which would smack too much of political inertia, denying ministers the machismo associated with repeated waves of public service reform.

Side-stepping problematic reforms

If only as much focus had been directed at reforming the financial services sector and channelling resources into wealth-creating investment; updating company law to accommodate the interests of all stakeholders; strengthening research and development; or raising the status of vocational education and skills training. How much more productively might our economy have performed as a consequence? How much more funding would accordingly have been available to modernise the country’s infrastructure and underpin essential public services?

It is a tale of missed opportunities. Government does of course have less direct leverage over the corporate sector. Under Theresa May, ‘industrial strategy’ is nonetheless again entering the political lexicon as we head towards a post-Brexit economy, alongside a £23bn National Productivity Investment Fund covered through additional borrowing and launched in the chancellor’s Autumn Statement. She also took on board corporate governance concerns, positioning herself after arriving in Downing Street in a place uncannily reminiscent of the ‘responsible capitalism’ advocated by former Labour leader Ed Miliband. Lobbying from powerful interests, however, appears to be taking its toll on initial radical intent.

And as the early years of the Blair premiership revealed, the impact of top-down reform on public services can itself be over-estimated.

© Dominic Lipinski - PA Wire

© Dominic Lipinski - PA Wire

The perpetual winter of Narnia

What is surprising indeed is how many of the basic problems that public services exist to address persist despite decades of reform: whether in the spheres of public and mental health; child protection and prevention of abuse of the elderly; re-offending rates; affordable housing; or ranking of educational outcomes in international league tables. The president of the Royal College of Surgeons, lamenting a health service close to breaking point and increasingly falling down on performance targets, used a graphic literary analogy: “It feels as if the NHS has stepped through the wardrobe and into the perpetual winter of Narnia!”

This disappointing track record is attributable not least to a tendency to prioritise structural change over other performance variables – timely environmental scanning; strategic leadership and management committed to sustainable improvement; staff morale and motivation; stakeholder engagement; outcome-focused information systems; cost-effective deployment of resources; institutional capabilities; and organisational culture.

Structural tinkering temptingly offers the kudos of tangible quick hits. But not only is it too often surface in nature, it can be negatively disruptive. We now have the prospect of yet another structural ‘solution’ to the challenge of raising educational attainment, allowing existing selective grammar schools to expand and new ones to come into being, before the earlier academy programme has had sufficient time to become fully embedded. In this case a previously discredited system is being reinvented, taking us back to the future!

Public services should be constantly drawn towards innovation to improve quality and cost-effectiveness, induced so to do. Yet, we are driven inexorably to the conclusion that so many of the changes we have witnessed since the 1980s in fact amount to ‘pseudo’ reform.

© Jeff J Mitchell PA Wire/PA Images